Conceptual - NOMINEE: Aziza Murray

Aziza Murray

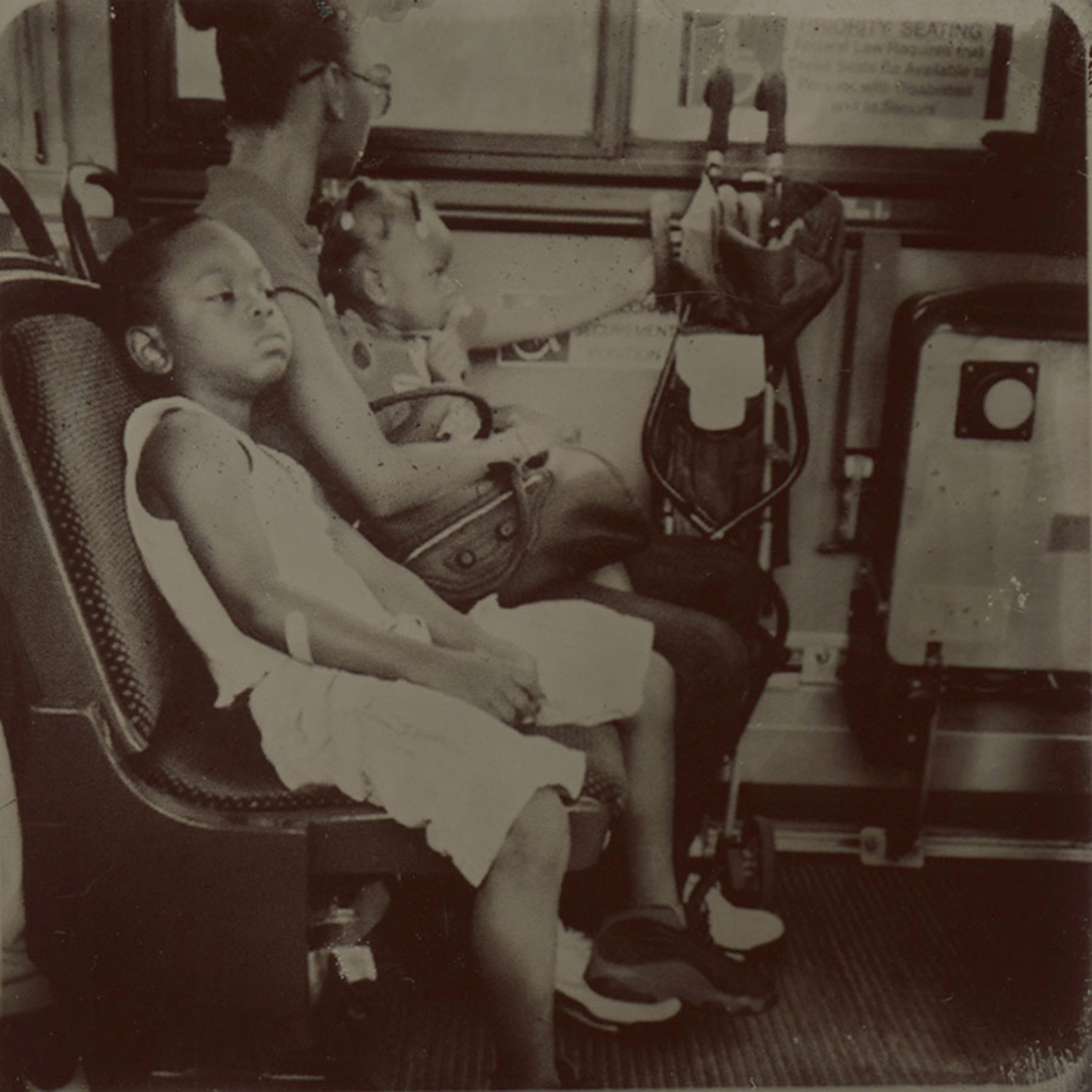

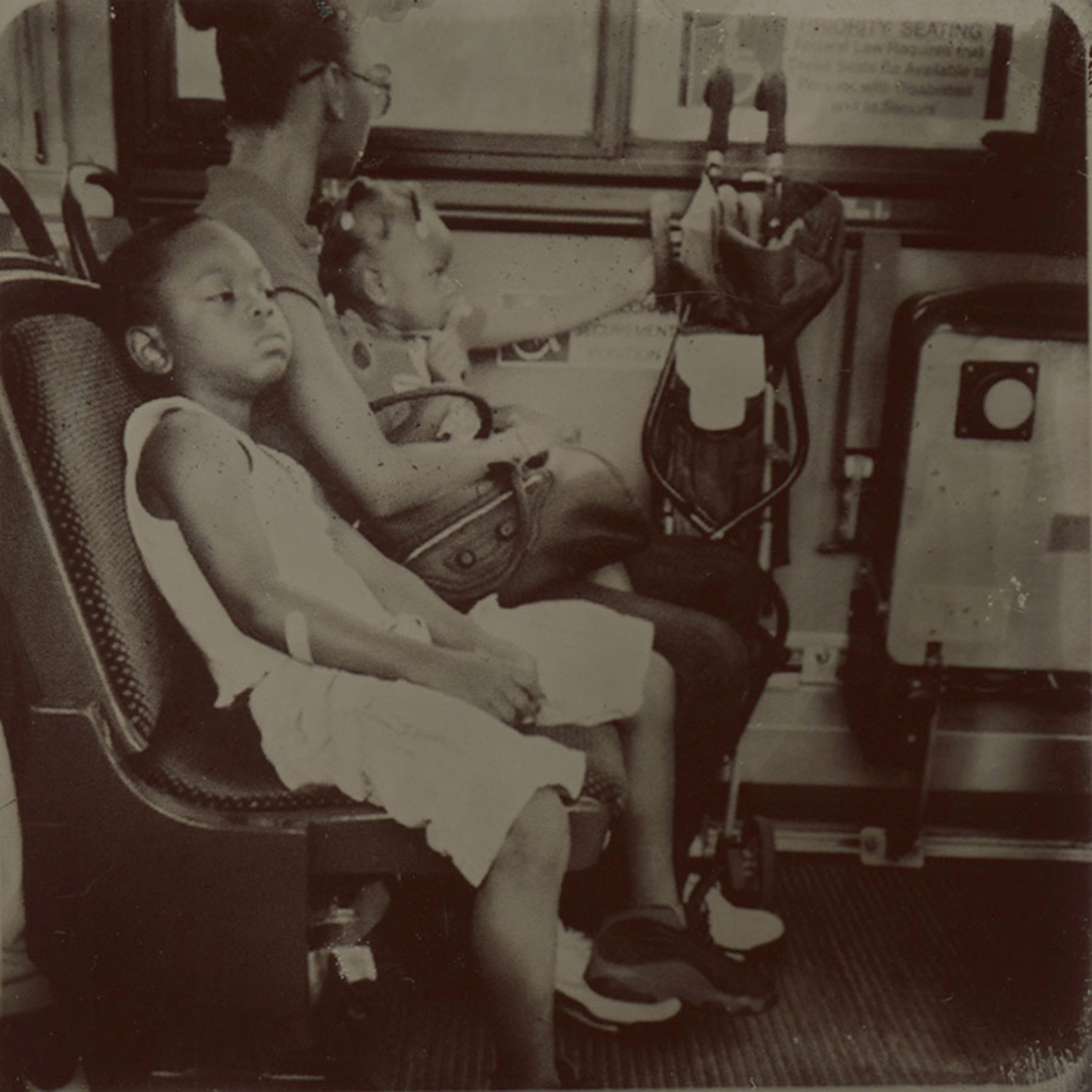

Tinstagrams

Support this photographer - share this work on Facebook.

The whole time I was participating in academia and Fine Art with a capital F-A while earning my MFA in photography, I was also engaging in a form of “low brow” art: I was posting my iPhone snapshots to Instagram. I documented everything: graffiti, my friends, pets, the New Mexico landscape, my travels back home, and ephemera I found beautiful. I was having fun and not overthinking these images the way I seemed to overthink everything else I made. Instead of trying to force a concrete message from the art I was creating in my academic life, or an end to a body of work, I began to legitimize my Instagram snapshots and connect them with historical snapshot photography.

I think the first tintypes I ever saw were of my maternal great, great grandparents, Sally and Xeno Tingle; two very serious, austere-looking people; non-smiling, Sally’s curls plastered to her forehead in what I assume was the fashion of that era (sometime in the late 1800s). One of the tintypes had their infant son in it, tow-headed and just as serious. It was fascinating to look at these images of people whose lives I can only speculate about because of a lack of written information about them, but know that they were my blood relations. In addition to this interesting family history, I loved the solidity of the tintypes, the blackened backs of the metal and the pointy corners. Photo historian, writer and curator Geoffrey Batchen said:

“Where the silvery daguerreotype image was easily damaged and highly reflective and thus difficult to see, tintypes had a dull but stable surface that invited handling and close looking. Indeed many of these small tintypes were touched as much as they were seen (touching and seeing became complementary stages of the same photographic encounter). Inexpensive and durable, tintypes invited a physical intimacy denied by other kinds of imagery.”

Batchen goes on to call the tintype, “the progenitor of the American snapshot and the millions of digital images that are today uploaded to sites such as Flickr, MySpace, and Facebook. (And I will add Instagram) “The importance of these democratic forms is immense,” he says.

The ubiquity of smartphones and the ease with which Instagram allows for the creation and dissemination of images can enable the average person to freeze important and mundane moments in his or her life, adding to an online collection of images of universal events and topics, from weddings to what they ate for breakfast. It simultaneously elevates and cheapens photography, making it easy for anyone with access to a smartphone to become a photographer. Because of this, I sometimes have a love/hate relationship with it, but, I loved looking at the tiny images I made on the small screen of my iPhone, liked knowing that I had a whole digital catalog of my own work as well as access to others’ on this little device in my pocket.

The tactile quality of older snapshots was still lacking though. People generally don’t print their snapshots anymore; instead these images remain hovering in digital libraries on phones tucked into people’s back pockets or in online Facebook albums, never occupying physical space. Contemporary snapshots lack tangibility in a culture that is oversaturated with imagery, particularly online. Photographs are viewed through the cold, blue light wavelengths emanating from phones, tablets, and laptops. I knew that printing these images digitally was not the answer I sought.

Stirred by the instant gratification of an Instagram photo and my love of darkroom processes, I decided to combine the two. I made transparencies of selected photographs that I had uploaded to Instagram, and I used them like negatives in an enlarger in the darkroom. I printed the images on brown lacquered aluminum plates coated with collodion, relatively the size they would appear on an iPhone screen, keeping them small and allowing for an intimate viewing experience. Using brown aluminum instead of black was an aesthetic choice that is in keeping with the short “chocolate” tintype period that began in the early 1870s. In many of the images, traces of the chemical process are visible as light, rainbow streaks or spots where there may have been air bubbles in the collodion, or places where the collodion was a little too thick. All are marks of my hand in the process.

Inspired by some of the beautiful and delicate embossments framing tintypes I had seen in thrift stores and online, I collaborated with another artist to learn how to make my own embossed frames for my tintypes. Borrowing designs I found online, I customized them in Photoshop and used an etching process to create plates that I ran through a press with mat board.

The results of this hybridization of processes satisfied my craving for permanence and tangibility in my work.

About author:

Aziza Murray is a New Mexico based artist working primarily in photography. In 2015 she graduated with an MFA from the University of New Mexico where she also worked as a pictorial archiving fellow for the Center for Southwest Research. Since then, Aziza has worked in different capacities in the film industry in Santa Fe and Albuquerque, further piquing her interest in cinematography. Much of her work stems from a well of nostalgia for objects and moments, the materiality of photography, and her personal history–from experiencing tragic loss at an early age, to her multilayered experiences as a biracial person growing up in Washington, DC. She has shown her work in DC at Connersmith Contemporary and in Albuquerque at the Harwood Art Center, the Bernalillo County Courthouse and, the UNM Art Museum. Currently Aziza has work in the National Hispanic Cultural Center’s group show Because It’s Time: Unraveling Race and Place in NM.